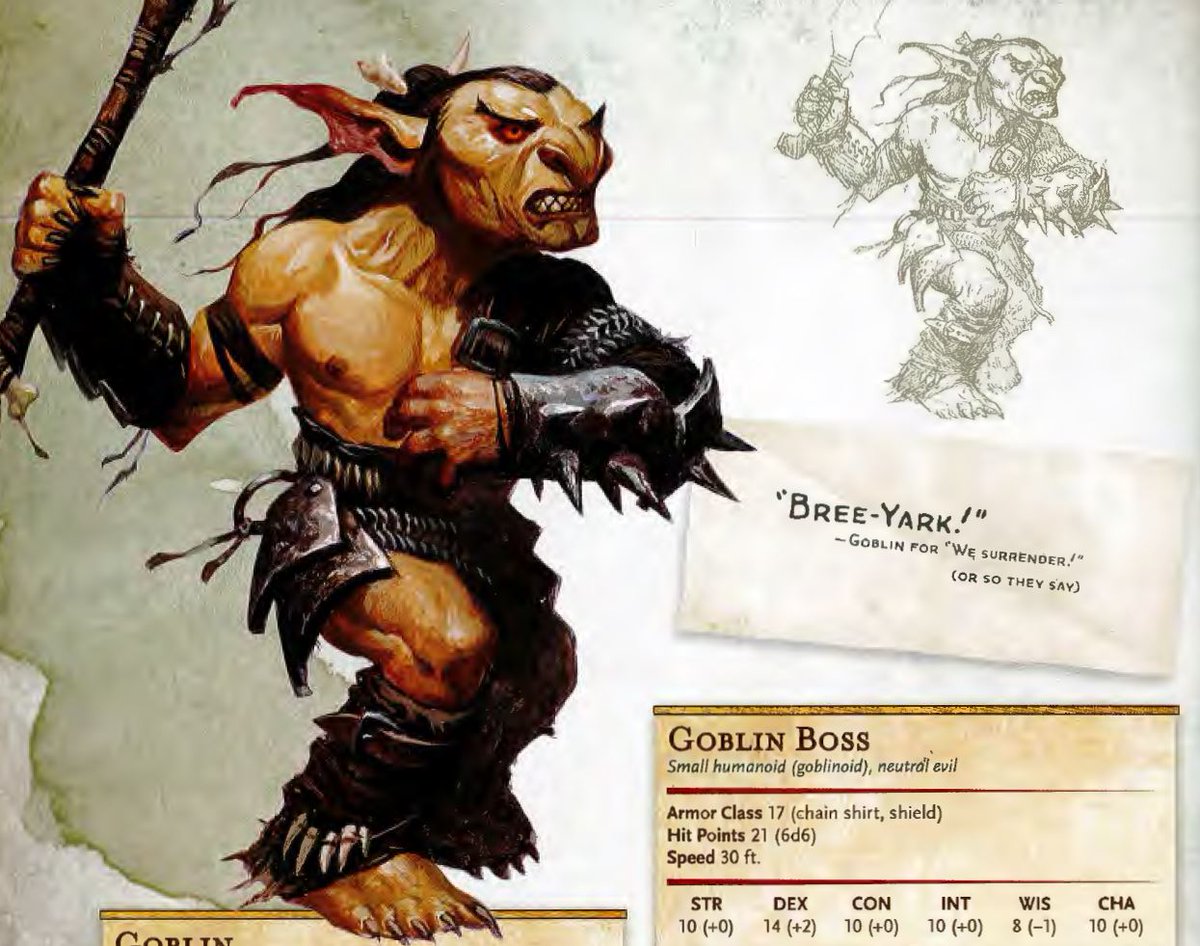

Fresh D&D campaign with some Abnib folks! I’m playing a Harengon Barbarian.

I’m a fierce bunny rabbit!

Dan Q

Last night I had a nightmare about Dungeons & Dragons. Specifically, about the group I DM for on alternate Fridays.

In their last session the party – somewhat uncharacteristically – latched onto a new primary plot hook rightaway. Instead of rushing off onto some random side quest threw themselves directly into this new mission.

This effectively kicked off a new chapter of their story, so I’ve been doing some prep-work this last week or so. Y’know: making battlemaps, stocking treasure chests with mysterious and powerful magical artefacts, and inventing a plethora of characters for the party to either befriend or kill (or, knowing this party: both).

Anyway: in the dream, I sat down to complete the prep-work I want to get done before this week’s play session. I re-checked my notes about what the adventurers had gotten up to last time around, and… panicked! I was wrong, they hadn’t thrown themselves off the side of a city floating above the first layer of Hell at all! I’d mis-remembered completely and they’d actually just ventured into a haunted dungeon. I’d been preparing all the wrong things and now there wasn’t time to correct my mistakes!

This is, of course, an example of the “didn’t prepare for the test” trope of dreams. Clearly I’m still feeling underprepared for this week’s game! But probably a bigger reason for the dream, and remembering it, was that I’ve had a cold and kept waking up to cough.

Right, better do a little more prep work!

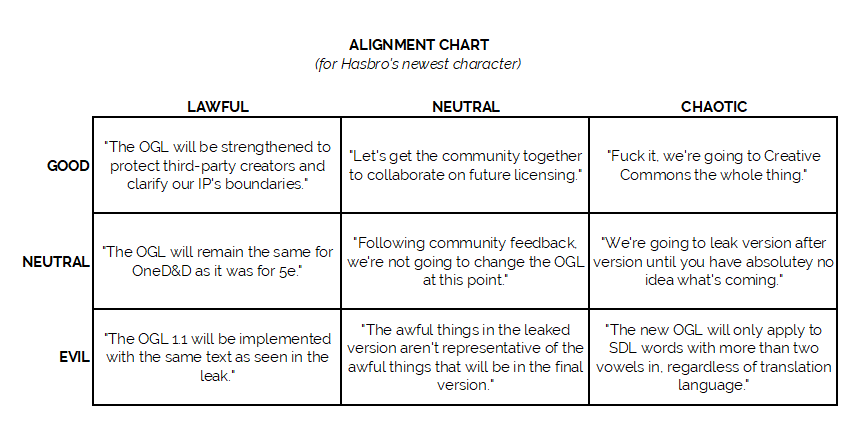

Hasbro seem to be rolling up a new character. Maybe this’ll help them.

This article is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

JTA tweeted a brilliant thread about something he discovered while digging through old D&D texts, and it’s awesome so – as I imagine he wouldn’t mind – I’ve reproduced it in full here:

I don’t really Twitter so much these days because like most social media it makes me either gloomy or extremely grumpy with the state of the world, but since I also lack the time to bother blogging anywhere, here’s a ludicrously nerdy thread about a Dungeons & Dragons rumour.So, back in the days of AD&D 1st Edition your printed modules would often come with a table of Rumours. The idea was hearing rumours increased the depth of the world, so players didn’t feel like NPCs just winked into existence when they entered the Hydra’s Den tavern & said “hi”.

But sometimes the rumours would be false, or exaggerated. That also added depth and had the bonus of ensuring that players didn’t take it for granted. OK, this guy in the red robe *says* Kobolds are poisoning the iron ore, but is that at all plausible, or is it just a bad seam?

(Those of us without any friends, or at least without friends equally into D&D in the 80s & 90s, also got this experience because it was well-replicated in the TSR Gold Box series of games, either in-game, or more-commonly through supplementary material in the boxes.

The supplementary materials often came in a separate “Journal” supplied in the box, & were a sort of additional layer of copy-protection because if the Game says “read Entry 19”, your choice is either do so, or wait 25 years for the abandonware PDFs to hit archive.org.

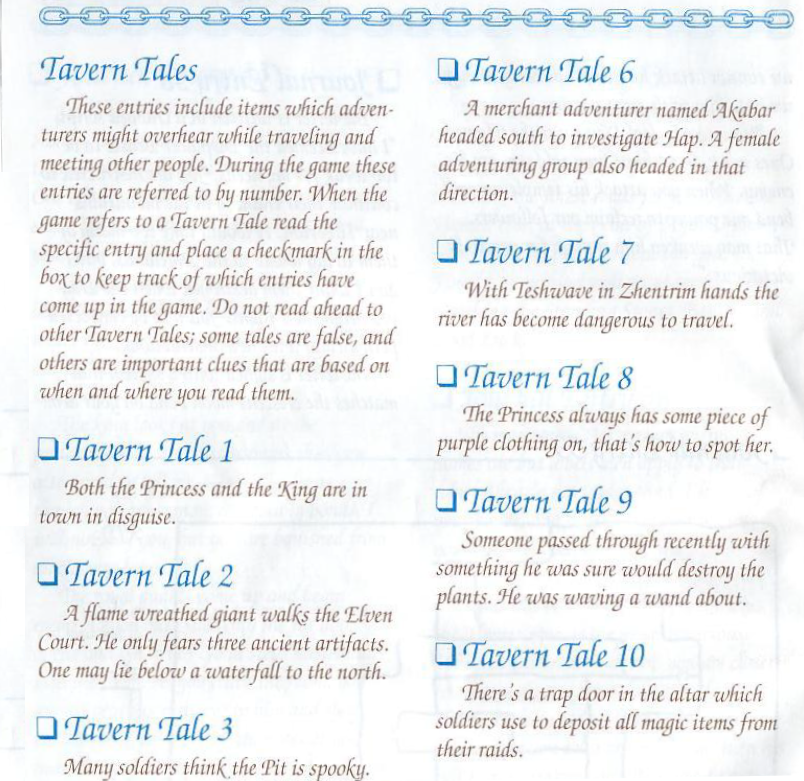

e.g., here’s the Traveller’s Tales from ‘Curse of the Azure Bonds’: note the subtlety of entries 1 and 8, about the Princess, sounding corroborative – maybe encouraging the party to more deference around someone with purple in their clothes, though either or both might be false.)

Anyway, this only really existed in the TSR/SSI games because it was in the standard modules.

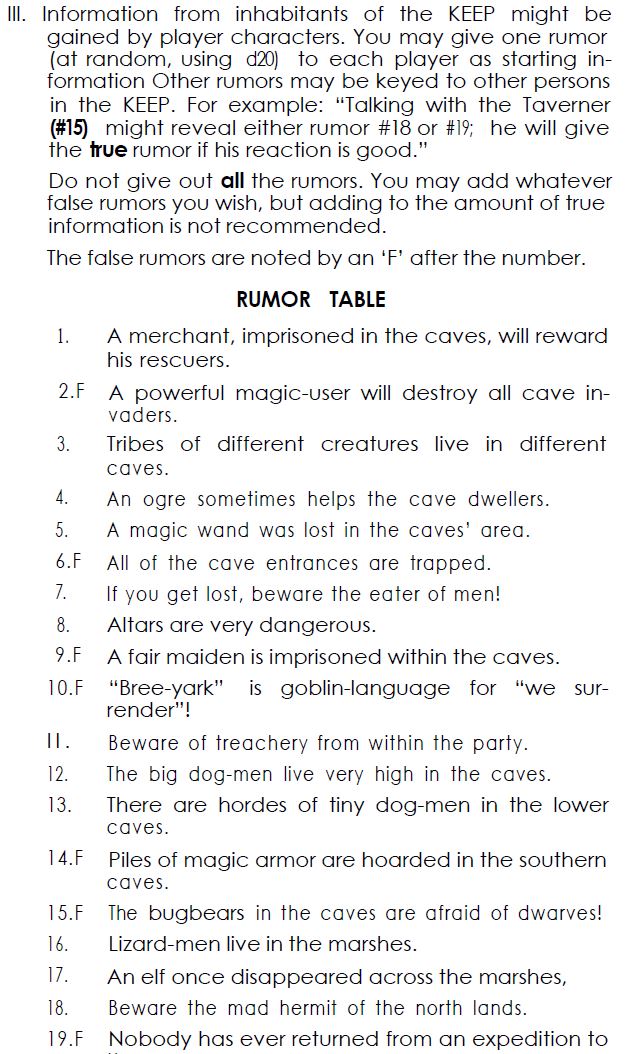

I was reminded of the rumour system when I was digging back into AD&D Module B2: The Keep on the Borderlands to borrow a bunch of content for a campaign I’ve just inherited (as you do)

‘Keep on the Borderlands’ was by Gary Gygax himself, and suffers a bunch from the typical issues 1e had, none of which I’ll address here because I would please nobody. But the rumours table is a really good example of the type – it gives players depth but not unfair advantages.

Now Keep on the Borderlands was a pretty big deal of a module back in the day. It was module B2, of the Basic Set, & it did some stuff really well, especially for new players – sort of a 1980 equivalent of ‘Lost Mine of Phandelver’ today. Lots of players cut their teeth on it.

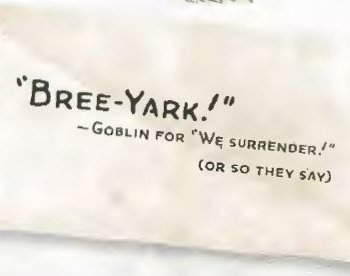

Rumour 10 – ‘”Bree-Yark” is goblin-language for “we surrender”!’ – is a false rumour, though the party doesn’t know that: whatever ‘Bree-yark’ means, it’s not “We Surrender”.

In fact, the module tells the DM it means “Hey, rube!!” and is used by goblins to sound the alarm.

(Spoilers here for the Goblin Lair in Location D of the Caves of Chaos, but when goblins on watch call out “Bree-yark!”, more goblins at #18 will bribe an ogre to come help attack the party. (1e often imposed dynamic worlds by fiat, back when the world was young, the DMs green)

So lots of early DMs got to imagine the potential hilarity of the party arriving in the cave, hearing goblins apparently surrendering, & dropping their guard, never realising life just got harder!

(It isn’t much hilarity, but in the 80s, as now, there was limited scope for joy)

Still – it’s a decent joke. Everyone believes “Bree-yark” is Goblin for surrender, but it isn’t really, that’s just a false rumour, spread by boastful drunks who’ve never seen a goblin in real life anyway.

So much for 1st Edition AD&D, I guess.

…except:

It’s 2014. The wheel of time turns, ages come and pass, and Grapple rules don’t so much become legend as “remain completely incomprehensible”. Now every new adventurer carries a Field Marshall’s baton in their knapsack, ‘cos tracking encumbrance is for chumps, & D&D 5e launches.

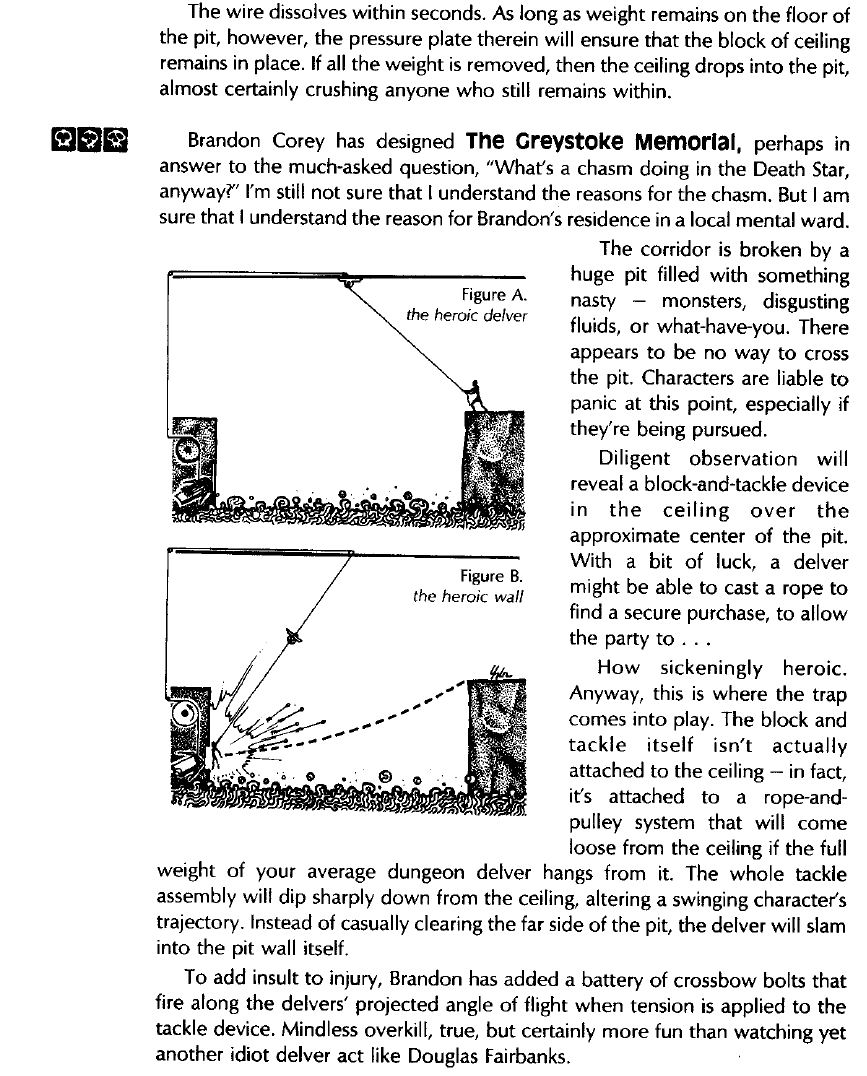

(While I’m doing archaeology, take a moment in this fast-forward to enjoy the glorious madness of the Grimtooth’s Traps series, which popped up in ’81 & features brilliantly inventive nastiness to spring on players who aren’t too attached to their character sheets. Or friends.)

So, 5e launches, to a lot of stick in some circles (I never knew a version of D&D that didn’t: probably some wazzock in 1971 ranted that the codified Fantasy Supplement rules in ‘Chainmail’ “beTraYs rEaL FaNs!” and sold out the hobby, but at least they couldn’t whinge on Reddit)

…but someone involved in 5e is has conjured the most obscurely brilliant bit of ultra-specific nerd humour I have seen in years.

Y’see, 5e modules don’t really do Rumour Tables or “If the party X, then Y, else Z” – DMs create dynamic worlds on the fly. (Hopefully).

So you’d think there’s no more chance of hilarious moments where the Goblins start yelling “Bree-Yark!” and Magnus Rushes In only to be shocked to find a well-bribed and high-Challenge Rating ogre running obediently up from Location E.22.

But you would think (slightly) wrong.

Because although 5e modules don’t do rumours the like 1e did, the Monster Manual does do flavour text – it’s usually a snippet of lore, or a word from a famous scholar, or advice from an adventurer who encountered the monster but lived to tell the tale. It provides fluffy depth.

And, actually, I say “it’s usually” but I’ve just checked and every bit of flavourtext I can find in the Monster Manual is either By A Scholar, From a Book, An Adventurer’s Tale, or a Monster Describing Itself…

…with one single exception: the flavourtext on the entry for Goblins, which isn’t attributed to anybody or anything, but is just the claim that “Bree-Yark!” means “we surrender!”

This isn’t attributed to any source. Nobody in-lore has a citation for this. It’s just something “they say”. A genuine 1st Edition rumour just chilling out in the 5th edition Monster Manual three decades after B2 landed.

Glorious. Well played, @Wizards. Very well played.

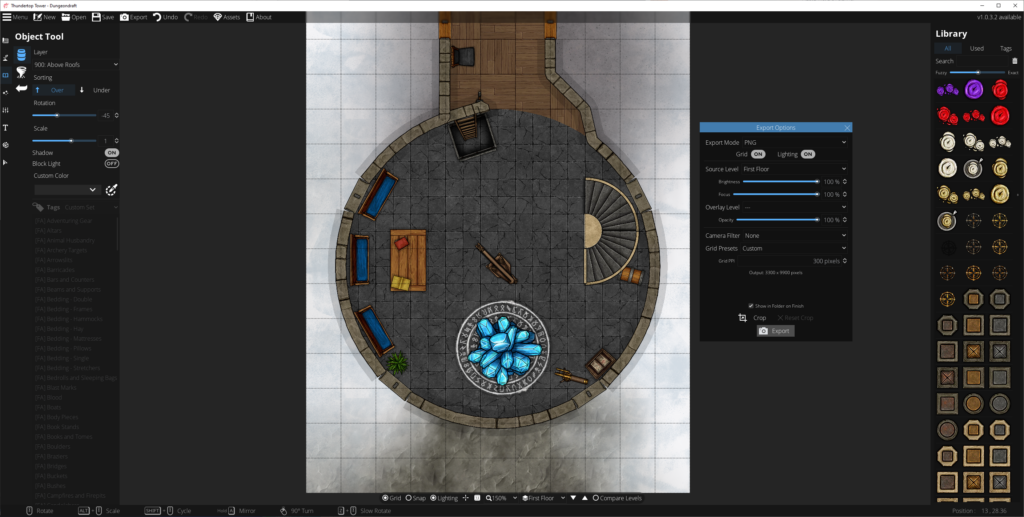

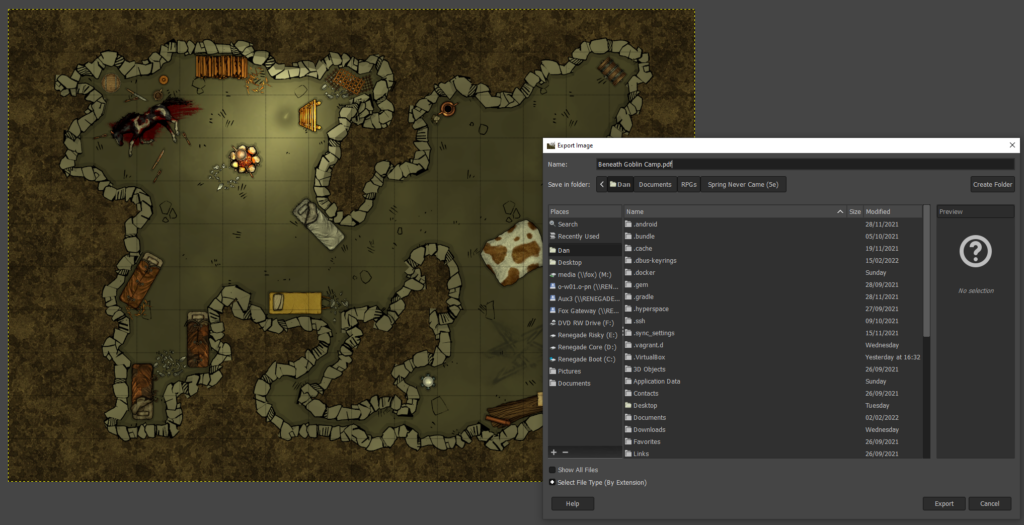

I really love Dungeondraft, an RPG battle map generator. It’s got great compatibility with online platforms like Foundry VTT and Roll20, but if you’re looking to make maps for tabletop play, there’s a few tips I can share:

Dungeondraft has (or can be extended with) features to support light levels and shadow-casting obstructions, openable doors and windows, line-of sight etc… great to have when you’re building for Internet-enabled tabletops, but pointless when you’re planning to print out your map! Instead:

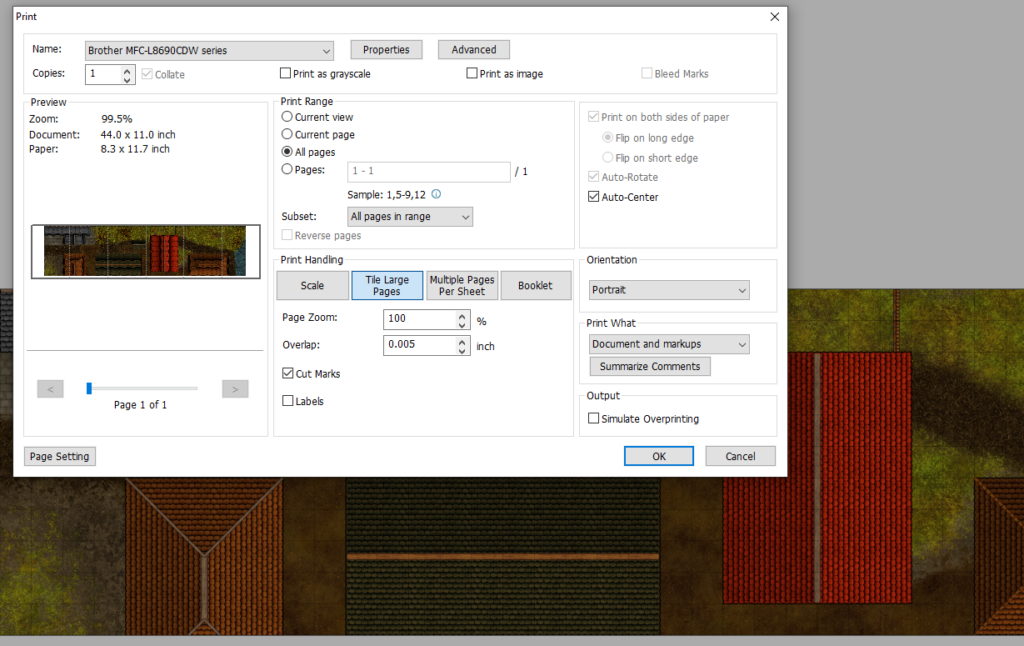

There’s no “print” option in Dungeondraft, so – especially if your map spans multiple “pages” – you’ll need a multi-step process to printing it out. With a little practice, it’s not too hard or time-consuming, though:

Export your map (level by level) from Dungeondraft as PNG files. The default settings are fine, but pay attention to the “Overlay level” setting if you’re using smart or complex cover-ups as described above.

To easily spread your map across multiple pages, you’ll need to convert it to a PDF. I’m using Gimp to do this. Simply open the PNG in Gimp, make any post-processing/last minute changes that you couldn’t manage in Dungeondraft, then click File >

Export As… and change the filename to have a .pdf extension. You could print directly from Gimp, but in my experience PDF reader software does a much better job at multi-page printing.

Open your PDF in an appropriate reader application with good print management. I’m using Foxit, which is… okay? Print it, selecting “tile large pages” to tell it to print across multiple sheets. Assuming you’ve produced a map an appropriate size for your printer’s margins, your preview should be perfect. If not, you can get away with reducing the zoom level by up to a percent or two without causing trouble for your miniatures. If you’d like the page breaks to occur at specific places (for exposure/reveal reasons), go back to Gimp and pad one side of the image by increasing the canvas size.

Check the level of “overlap” specified: I like to keep mine low and use the print margins as the overlapping part of my maps when I tape them together, but you’ll want to see how your printer behaves and adapt accordingly.

If you’re sticking together multiple pages to make a single large map, trim off the bottom and right margins of each page: if you printed with cut marks, this is easy enough even without a guillotine. Then tape them together on the underside, taking care to line-up the features on the map (it’s not just your players who’ll appreciate a good, visible grid: it’s useful when lining-up your printouts to stick, too!).

I keep my maps rolled-up in a box. If you do this too, just be ready with some paperweights to keep the edges from curling when you unfurl them across your gaming table. Or cut into separate rooms and mount to stiff card for that “jigsaw” effect! Whatever works best for you!

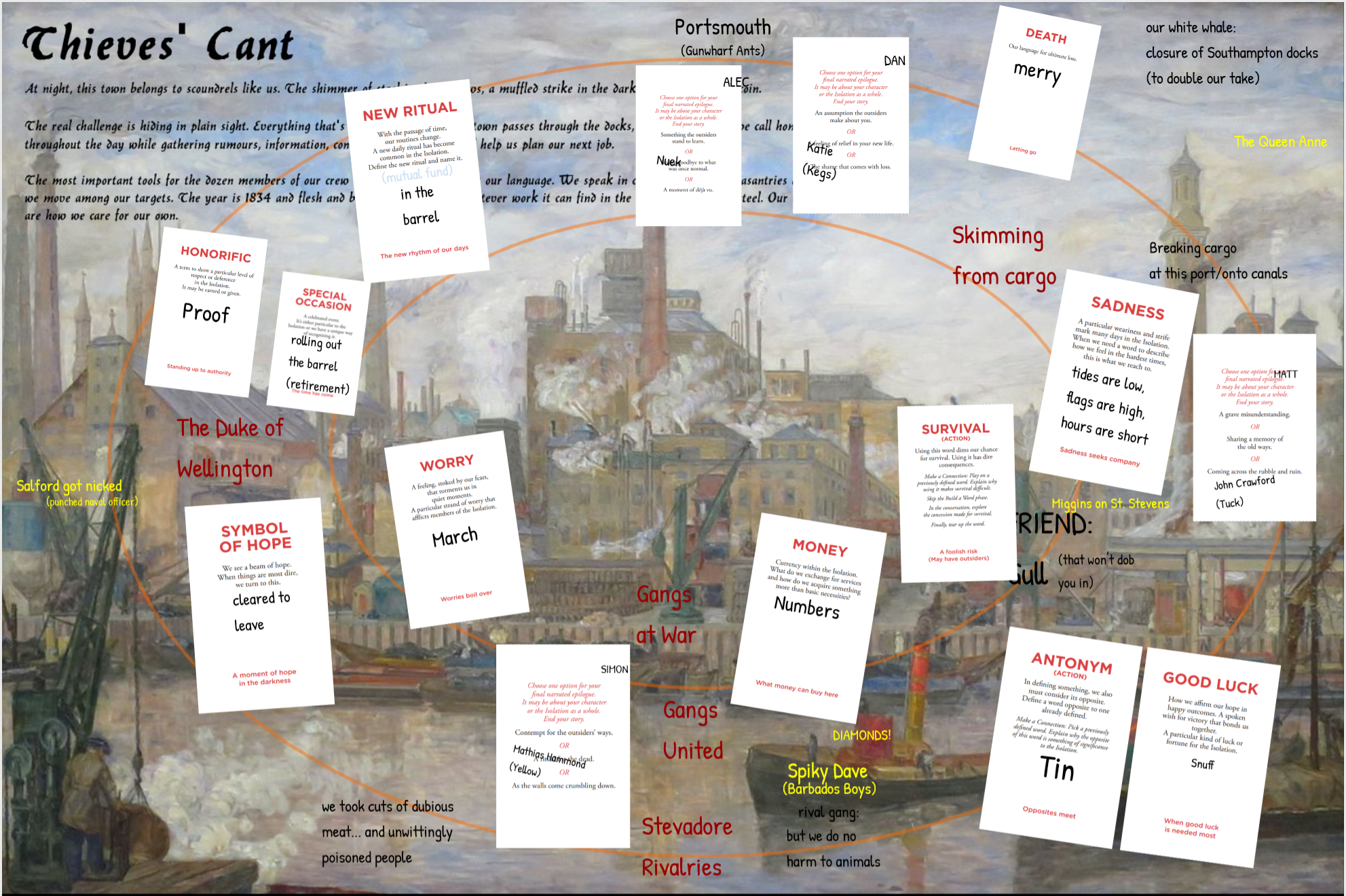

Following the success of our last game of Dialect the previous month and once again in a one-week hiatus of our usual Friday Dungeons & Dragons game, I hosted a second remote game of this strange “soft” RPG with linguistics and improv drama elements.

Our backdrop to this story was Portsmouth in 1834, where we were part of a group – the Gunwharf Ants – who worked as stevedores and made our living (on top of the abysmal wages for manual handling) through the criminal pursuit of “skimming a little off the top” of the bulk-break cargo we moved between ships and onto and off the canal. These stolen goods would be hidden in the basement of nearby pub The Duke of Wellington until they could be safely fenced, and this often-lucrative enterprise made us the envy of many of the docklands’ other criminal gangs.

I played Katie – “Kegs” to her friends – the proprietor of the Duke (since her husband’s death) and matriarch of the group. I was joined by Nuek (Alec), a Scandinavian friend with a wealth of criminal experience, John “Tuck” Crawford (Matt), adoptee of the gang and our aspiring quartermaster, and “Yellow” Mathias Hammond (Simon), a navy deserter who consistently delivers better than he expects to.

While each of us had our stories and some beautiful and hilarious moments, I felt that we all quickly converged on the idea that the principal storyline in our isolation was that of young Tuck. The first act was dominated by his efforts to proof himself to the gang, and – with a little snuff – shake off his reputation as the “kid” of the group and gain acceptance amongst his peers. His chance to prove himself with a caper aboard the Queen Anne went proper merry though after she turned up tin-ful and he found himself kept in a second-place position for years longer. Tuck – and Yellow – got proofed eventually, but the extra time spent living hand-to-mouth might have been what first planted the seed of charity in the young man’s head, and kept most of his numbers out of his pocket and into those of the families he supported in the St. Stevens area.

The second act turned political, as Spiky Dave, leader of the competing gang The Barbados Boys, based over Gosport way, offered a truce between the two rivals in exchange for sharing the manpower – and profits – of a big job against a ship from South Africa… with a case of diamonds aboard. Disagreements over the deal undermined Kegs’ authority over the Ants, but despite their March it went ahead anyway and the job was a success. Except… Spiky Dave kept more than his share of the loot, and agreed to share what was promised only in exchange for the surrender of the Ants and their territory to his gang’s rulership.

We returned to interpersonal drama in the third act as Katie – tired of the gang wars and feeling her age – took perhaps more than her fair share of the barrel (the gang’s shared social care fund) and bought herself clearance to leave aboard a ship to a beachside retirement in Jamaica. She gave up her stake in the future of the gang and shrugged off their challenges in exchange for a quiet life, leaving Nuek as the senior remaining leader of the group… but Tuck the owner of the Duke of Wellington. The gang split into those that integrated with their rivals and those that went their separate ways… and their curious pidgin dissolved with them. Well, except for a few terms which hung on in dockside gang chatter, screeched amongst the gulls of Portsmouth without knowing their significance, for years to come.

Despite being fundamentally the same game and a similar setting to when we played The Outpost the previous month, this game felt very different. Dialect is versatile enough that it can be used to write… adventures, coming-of-age tales, rags-to-riches stories, a comedies, horror, romance… and unless the tone is explicitly set out at the start then it’ll (hopefully) settle somewhere mutually-acceptable to all of the players. But with a new game, new setting, and new players, it’s inevitable that a different kind of story will be told.

But more than that, the backdrop itself impacted on the tale we wove. On Mars, we were physically isolated from the rest of humankind and living in an environment in which the necessities of a new lifestyle and society necessitates new language. But the isolation of criminal gangs in Portsmouth docklands in the late Georgian era is a very different kind: it’s a partial isolation, imposed (where it is) by its members and to a lesser extent by the society around them. Which meant that while their language was still a defining aspect of their isolation, it also felt more-artificial; deliberately so, because those who developed it did so specifically in order to communicate surreptitiously… and, we discovered, to encode their group’s identity into their pidgin.

While our first game of Dialect felt like the language lead the story, this second game felt more like the language and the story co-evolved but were mostly unrelated. That’s not necessarily a problem, and I think we all had fun, but it wasn’t what we expected. I’m glad this wasn’t our first experience of Dialect, because if it were I think it might have tainted our understanding of what the game can be.

As with The Outpost, we found that some of the concepts we came up with didn’t see much use: on Mars, the concept of fibs was rooted in a history of of how our medical records were linked to one another (for e.g. transplant compatibility), but aside from our shared understanding of the background of the word this storyline didn’t really come up. Similarly, in Thieves Cant’ we developed a background about the (vegan!) roots of our gang’s ethics, but it barely got used as more than conversational flavour. In both cases I’ve wondered, after the fact, whether a “flashback” scene framed from one of our prompts might have helped solidify the concept. But I’m also not sure whether or not such a thing would be necessary. We seemed to collectively latch onto a story hook – this time around, centred around Matt’s character John Crawford’s life and our influences on it – and it played out fine.

And hey; nobody died before the epilogue, this time!

I’m looking forward to another game next time we’re on a D&D break, or perhaps some other time.

This week our usual Dungeons & Dragons group took a week off while our DM recovered from a long and tiring week. As a “filler”, I offered to facilitate a game of Dialect: A Game About Language and How It Dies, from Thorny Games, who I discovered through a Metafilter post about their latest free print-and-play game, Sign: A Game about Being Understood. Yes, all of their games about about language and communication; what of it?

Dialect could be described as a rules-light, GM-less (it has a “facilitator” role, but they have no more authority than any player on anything), narrative-driven/storytelling roleplaying game based on the concept of isolated groups developing their own unique dialect and using the words they develop as a vehicle to tell their stories.

This might not be the kind of RPG that everybody likes to play – if you like your rules more-structured, for example, or you’re not a fan of “one-shot”/”beer and pretzels” gaming – but I was able to grab a subset of our usual roleplayers – Alec, Matt R, Penny, and I – and have a game (with thanks to Google Meet for videoconferencing and Roll20 for the virtual tabletop: I’d have used Foundry but its card support is still pretty terrible!).

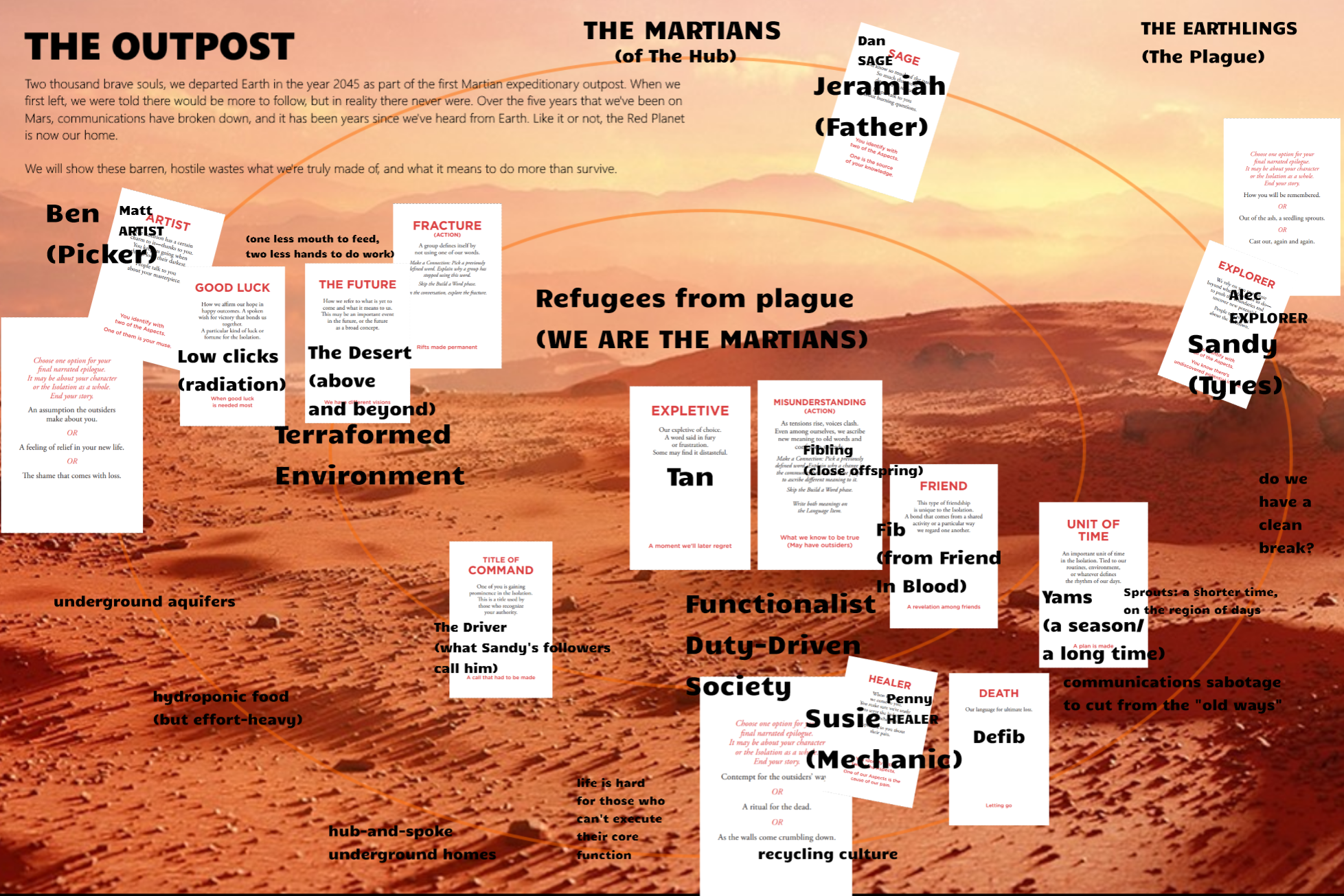

A game of Dialect begins with a backdrop – what other games might call a scenario or adventure – to set the scene. We opted for The Outpost, which put the four of us among the first two thousand humans to colonise Mars, landing in 2045. With help from some prompts provided by the backdrop we expanded our situation in order to declare the “aspects” that would underpin our story, and then expand on these to gain a shared understanding of our world and society:

It soon became apparent that communication with Earth had been severed, at least initially, from our end: radicals, seeing the successes of our new social and economic systems, wanted to cement our differences by severing ties with the old world. And so our society lives in a hub-and-spoke cave system beneath the Martian desert, self-sustaining except for the need to send rovers patrolling the surface to scout for and collect valuable surface minerals.

In this world, and prompted by our cards, we each developed a character. I was Jeramiah, the self-appointed “father” of the expedition and of this unusual new social order, who remembers the last disasters and wars of old Earth and has revolutionary plans for a better world here on Mars, based on controlled growth and a planned economy. Alec played Sandy – “Tyres” to their friends – a rover-driving explorer with one eye always on the horizon and fresh stories for the colony brought back from behind every new crater and mountain. Penny played Susie, acting not only as the senior medic to the expedition but something more: sort-of the “mechanic” of our people-driven underground machine, working to keep alive the genetic records we’d brought from Earth and keep them up-to-date as our society eventually grew, in order to prevent the same kinds of catastrophe happening here. “Picker” Ben was our artist, for even a functionalist society needs somebody to record its stories, celebrate its accomplishments, and inspire its people. It’s possible that the existence of his position was Jeramiah’s doing: the two share a respect for the stark, barren, undeveloped beauty of the Martian surface.

We developed our language using prompt cards, improvised dialogue, and the needs of our society. But the decades that followed brought great change. More probes began to land from Earth, more sophisticated than the ones that had delivered us here. They brought automated terraforming equipment, great machines that began to transform Mars from a barren wasteland into a place for humans to thrive. These changes fractured our society: there were those that saw opportunity in this change – a chance to go above ground and live in the sun, to expand across the planet, to make easier the struggle of our day-to-day lives. But others saw it as a threat: to our way of life, which had been shaped by our challenging environment; to our great social experiment, which could be ruined by the promise of an excessive lifestyle; to our independence, as these probes were clearly the harbingers of the long-promised second wave from Earth.

Even as new colonies were founded, the Martians of the Hub (the true Martians, who’d been here for yams time, lived and defibed here, not these tanning desert-dwelers that followed) resisted the change, but it was always going to be a losing battle. Jeramiah took his last breath in an environment suit atop a dusty Martian mountain a day’s drive from the Hub, watching the last of the nearby deserts that was still untouched by the new green plants that had begun to spread across the surface. He was with his friend Sandy, for despite all of the culture’s efforts to paint them as diametrically opposed leaders with different ideas of the future, they remained friends until the end. As the years went by and more and more colonists arrived, Sandy left for Phobos, always looking for a new horizon to explore. Sick of the growing number of people who couldn’t understand his language or his art, Ben pioneered an expedition to the far side of the planet where he lived alone, running a self-sustaining agri-home and exploring the hills until his dying day. We were never sure where Susie ended up, but it wasn’t Mars: she’d talked about joining humanity’s next big jump, to the moons of Jupiter, so perhaps she’s out there on one of the colonies of Titan or Europa. Maybe, low clicks, she’s even keeping our language alive out there.

The whole event was a lot of fun and I’m keen to repeat it, perhaps with a different group and a different backdrop. The usual folks know who they are, but if you’re not one of those and you want in next time we play, drop me a message of some kind.

This article is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

This article is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

…

Goats are the main characters. You are the supporting cast.

This game is about running mind-blowing live action experiences for goats. You will act as director and storyteller, transporting the goats to an unforgettable dream world of mystery and magic, etc etc.

Goat Larp is one part larp, one part hangout-with-animals-and-take-silly-pictures. In some ways, we are roleplaying that this is a larp.

The Goat Larp Rulebook

Rule number 1 through 100 is BE NICE TO THE GOATS.

Your Character

Show up at the farm dressed as any character you want. You could be an elf, a steampunk, the mayor of space, Hulk Hogan, Darth Vader, whatever.

Your character has no knowledge of how you got to this mystical goat farm, but you can sense that these goats are IMPORTANT. They need to be entertained. You need to run a larp for them.

Goat Activity Cards

There will be a stack of Goat Activity Cards. They are suggestions for activities you can do with the goats. For example:

One goat plays as Frodo, another will be Sauron. Use lawn posts to mark off an area representing Mount Doom. If Frodo visits Mount Doom before Sauron touches him, the world is saved. If Sauron touches Frodo, all is lost.

Another example:

President Goat’s cabinet must advise them on an important decision. The fate of the world is in this goat’s hands. One post is labeled “World Peace”, another post is labeled “Nuke Everything”. If President Goat bumps into a post, their decision is made.

Both teams may try to persuade the goats using any (safe) means they can come up. You are encouraged to ham it up, over-act, and monologue about what’s going on. This gives the goats a nice, immersive experience.

You may also come up with your own quests. In fact, you should, because most of the stuff we’re writing is garbage.

You can read more ideas for Goat Activities here.

…

Oh, I thought: it’s LARPing but with goats. You know, like Goat Yoga is yoga but with goats. Okay, fair enough: whatever floats your goat…

…but no, I was wrong. This isn’t so much LARPing with goats as LARPing for goats. As in: the goats are the player chatacters; any humans that happen to come along are mobs there for the entertainment of the goats.

The Internet remains a strange and wonderful window into a strange and wonderful world.

This article is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

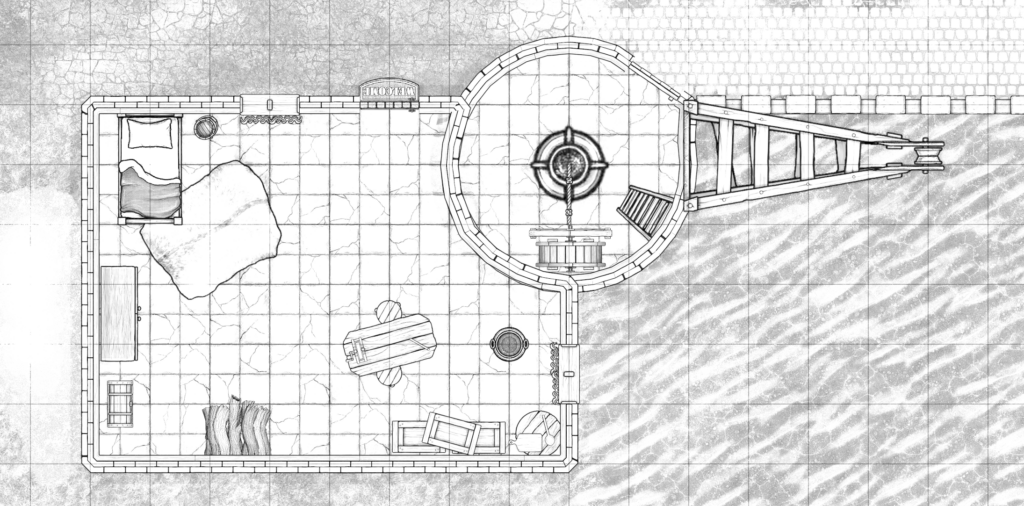

For the last few months, I’ve been GMing a GURPS campaign (that was originally a Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay 1st-edition campaign, in turn built upon a mixture of commercially published and homegrown modules, including, in turn, an AD&D module…) for a few friends.

So far, it’s included such gems as a player-written poem in a fictional language, another player’s drawing of the most-cinematic action sequence they’ve experienced so far… and the opportunity, during a play session that coincided with a player’s birthday, to explain the layout of a ruined tower by presenting them with a cake baked into the shape of the terrain.

If you’re interested in what we’ve been up to, the campaign has it’s own blog where you can read about the adventures of Newman, Bret, Lythil, Keru, and (the late) Sir Bea.

But mostly I wanted to make this post so that I had a point of context in case I ever get around to open-sourcing some of the digital tools I’ve been developing to help streamline our play sessions. For example, most of our battle maps and exploration are presented on a ‘board’ comprised of a flat screen monitor stripped of its stand and laid on its back, connected via the web to a tool that allows me to show, hide, or adapt parts of it from my laptop or mobile phone. Player stats, health, and cash, as well as the date, time, position of the sun as well as the phases of the moons are similarly tracked and are available via any player’s mobile phone at any time.

These kinds of tools have been popular for ‘long-distance’/Internet roleplaying for years, but I think there’s a lot of potential in locally-linked, tabletop-enhancing (rather than replacing) tools that deliver some of the same benefit to the (superior, in my opinion) experience of ‘proper’ face-to-face adventure gaming. Now, at least, when I tell you for example about some software I wrote to help calculate the position of the sun in the sky of a fictional world, you’ll have a clue why I would do such a thing in the first place.

This article is a repost promoting content originally published elsewhere. See more things Dan's reposted.

Commissioned, a webcomic I’ve been reading for many years now, recently made a couple of observations on the nature of “fetch quests” in contemporary computer role-playing games. And naturally – because my brain works that way – I ended up taking this thought way beyond its natural conclusion.

Today’s children are presumably being saturated with “fetch quests” in RPGs all across the spectrum from fantasy Skyrim-a-likes over to modern-day Grand Theft Auto clones and science fiction Mass Effect-style video games. And the little devil on my left shoulder asks me how this can be manipulated for fun and profit.

The traditional “fetch quest” goes as follows: I’ll give you what you need (the sword that can kill the monster, the job that you need to impress your gang, the name of the star that the invasion fleet are orbiting, or whatever), in exchange for you doing a delivery for me. Either I want you to take something somewhere, or I want you to pick something up, or – in the most overused and thankfully falling out of fashion example – I want you to bring me X number of Y object… 9 shards of triforce, 5 orc skulls, $10,000, or whatever. Needless to say, about 50% of the time there’ll be some kind of challenge along the way (you need to steal the item from a locked safe, you’ll be offered a bribe to “lose” the item, or perhaps you’ll just be mobbed by ninja robots as you ride along on your hypercycle), which is probably for the best because it’s the only thing that adds fun to role-playing a postman. I wonder if being attacked by mage princes is something that real-life couriers dream about?

This really doesn’t tally with normality. When you want something in the real world, you pay for it, or you don’t get it. But somehow in computer RPGs – even ones which allegedly try to model the real world – you’ll find yourself acting as an over-armed deliveryman every ten to fifteen minutes. And who wants to be a Level 38 Dark Elf Florist and Dog Walker?

So perhaps… just perhaps… this will begin to shape the future of our reality. If the children of today start to see the “fetch quest” as a perfectly normal way to introduce yourself to somebody, then maybe someday it will be socially acceptable.

I’m going to try it. The next time that somebody significantly younger than me looks impatient in the queue for the self-service checkouts at Tesco, I’m going to offer to let them go in front of me… but only if they can bring me a tin of sweetcorn! “I can’t go myself, you see,” I’ll say, “Because I need to hold my place in the queue!” A tin of sweetcorn may not be as impressive-sounding as, say, the Staff of Fire Elemental Control, but it gets the job done. And it’s one of your five-a-day, too.

Or when somebody asks me for help fixing their broken website, I’ll say “Okay, I’ll help; but you have to do something for me. Bring me the bodies of five doughnuts, to prove yourself worthy of my assistance.”

It’s going to be a big thing, I promise.

A couple of weeks ago, the other Earthlings and I played our very first game of Spirit of the Century. Spirit of the Century is a tabletop roleplaying game based on the FATE system (which in turn draws elements from the FUDGE system, and in particular, the FUDGE dice). Are you following me so far?

Spirit of the Century is set in the “pulp novel” era of the 1920s, in the optimistic period between the two world wars. The player characters play pulp-style heroes: the learned professor, the adventurous archaeologist, the daring pilot, all of those tropes of the era. Science, or – as it should be put – Science! is king, and there’s no telling what fantastic and terrifying secrets are about to be unleashed upon the world. Tell you what… let me just show you the cover for the sourcebook:

Everything you need to know about the game is right in that picture, right there.

The character generation mechanism is different from most RPGs; even other fluffy, anti-min/max-ey ones. All player characters (for reasons relevant to the mythos) were born on 1st January 1901, so the first part of character creation is explaining what they did during their childhood. The second part is about explaining what they did during the Great War. During each of these (and every subsequent step), the character will gain two “aspects”, which they’ll later use for or against their feats in a way not-too-dissimilar from the PDQ System (which may be familiar to those of you who’ve played Ninja Burger 2nd Edition).

The third chapter of character generation involves telling your character’s own story – their first adventure – in the style of a pulp novel. The back of the character sheet will actually end up with a “blurb” on it, summarising the plot of their novel. Then things get complicated. In the fourth and fifth chapters, each character will co-star in the novels of randomly-selected other player characters. This can involve a little bit of re-writing, as stories are bent in order to fit around the ideas of the players, but it serves an important purpose: it gives groups of player characters a collaborative backstory. “Remember the time that we fought off Professor Mechk’s evil robot army?”

That’s exactly what Johnny Sparks did in “Johnny Sparks and the Robot Army”. When Professor Mechk released his evil robot army on the streets of New York City, Johnny Sparks – government-sponsored whizkid – knew he had to act. With his old friend Jack Brewood (and Jack’s network of black market contacts), he acquired the parts to build a weapon powered by lightning itself. Then, alongside Mafia child and expert pugilist Michael Leone, he fought his way up the Empire State Building to Mechk’s control centre. While Michael duelled with Mechk, Johnny channeled the powers of the heavens into the gigantic robot brainwave transmitter at the top of the tower, sending it into overload. As the tower-top base melted down and exploded, Michael and Johnny abseiled rapidly down the side to safety.

And so they have a history, you see! And some “aspects” for it: Johnny got “Master of Storms” from his lightning-based research and “With thanks to Jack” for his friend’s support. Meanwhile Jack got “On Johnny’s wavelength” to represent the fact that he’s one of the few people who can follow Johnny’s strange and aspie-ish thought patterns.

In our first play session, Michael Leone (Paul), Jack Brewood (JTA), and Anna Midnight (Ruth) found themselves in a race to rescue aviator Charles Lindbergh from the evil Captain Hookshot and his blimp-riding pirates. Hookshot hoped to use the kidnap of Lindbergh as leverage to get his hands on some of Thomas Edison‘s secret research, which he hoped would allow him to gain a stranglehold on the world’s aluminium supply, which was only just beginning to be produced in meaningful quantities. So began an epic boat (and seaplane) chase across the Atlantic to mysterious Barnett Island, a fight through the pirates’ slave camp and bauxite mines, a Mexican-stand-off aboard a zeppelin full of explosives, and a high-speed escape from an erupting volcanic island.

Highlights included:

There’s a lot of potential for a lot of fun in this game, and we’ll be sure to play it again sometime soon.

[this post was damaged during a server failure on Sunday 11th July 2004, and it has not been possible to recover it]

[this post was partially recovered on 12 October 2018]

Yay! I won an eBay auction for a copy of Everyway. For £4! Yay! Winner! Now all I need are some friends, some paper, some pencils, and no dice.

In other good news, I solved a really nasty Project: Jukebox bug.

And finally: I’ve been spending way too long (when I should be revising) in Second Life. I’m currently working on trying to build the game world’s first Bluetooth-like short-range radio system, but while building prototypes I seem to have come up with a great espionage/surviellance device (i.e. a bug). It works really well. I’ve spent the afternoon listening in on people’s conversations. I intend to sell my bugging device for L$100 ($L = Linden Dollars, the currency of this virtual world), and then, when I’ve cornered the market, start selling a de-bugging device that can detect bug usage for L$500. I am one of those people, I have decided, whom; if I ran an anti-virus company, I would write viruses to ensure that people still needed my products.

I have one exam left. The …