Monopoly – the world’s best-selling board game – sucks. I’ve said it before, but it bears saying again. I’ve never made any secret of my distaste for the game, but it’s probably worth spelling out the reasons, in case you’ve somehow missed them.

Broadly-speaking, there are four things wrong with Monopoly: the rules, the theme, the history, and the players.

The Rules

The following issues have plagued Monopoly for at least the last 75 years:

- It takes a disproportionately long time to play, relative to the amount of fun it provides or skill it tests. A longer game is not intrinsically more-exciting: would a 1000-square Snakes & Ladders be ten times as good as a 100-square one? Monopoly involves a commitment of three to four hours, most of it spent watching other people take their turns.

- It’s an elimination game: players are knocked out (made bankrupt) one at a time, until only one remains. This invariably leads to a dull time for those players first removed from the game (compounded by the game length). In real-world play, it’s usually the case that a clear winner is obvious long before the game ends, leading to a protracted, painful, and frankly dull slow death for the other players. Compare this to strategic games like Power Grid, where it can be hard to call the winner between closely matched players right up until the final turns, in which everybody has a part.

- It depends hugely on luck, which fails to reward good strategic play. Even the implementation of those strategies which do exist remain heavily dependent on the roll of the dice. Contrast the superficially-simpler (and far faster) property game For Sale, which rewards strategic play with just a smidgen of luck.

- It’s too quick to master: you can learn and apply the optimal strategies after only a handful of games. Coupled with the amount of luck involved, there’s little to distinguish an expert player from a casual one: only first-time players are left out. Some have argued that this makes it easier for new players to feel like part of the game, but there are other ways to achieve this, such as handicaps, or – better – variable starting conditions that make the game different each time, like Dominion.

- There’s little opportunity for choice: most turns are simply a matter of rolling the dice, counting some spaces, and then either paying (or not paying) some rent. There’s a little more excitement earlier in the game, when properties remain unpurchased, but not much. The Speed Die add-on goes a small way to fixing this, as well as shortening the duration of the game, but doesn’t really go far enough.

- The rules themselves are ambiguously-written. If they fail to roll doubles on their third turn in jail, the rules state, the player much pay the fine to be released. But does that mean that they must pay, then roll (as per the usual mechanic), in which case must it be next turn? Or should it be this turn, and if so, should the already-made (known, non-double) roll be used? Similarly, the rules state that the amount paid when landing on a utility is the number showing on the dice: is this to be a fresh roll, or is the last roll of the current player the correct one? There are clarifications available for those who want to look, but it’s harder than it needs to be: it’s no wonder that people seem to make it up as they go along (see “The Players”, below, for my thoughts on this).

The Theme

But that’s not what Monopoly‘s about, is it? Its purpose is to instil entrepreneurial, capitalist values, and the idea that if you work hard enough, and you’re lucky enough, that you can become rich and famous! Well, that’s certainly not its original purpose (see “The History”, below), but even if it were, Monopoly‘s theme is still pretty-much broken:

- It presents a false financial model as if it were a reassuring truth. “The Bank can never go bankrupt,” state the rules, instructing us to keep track of our cash with a pen and paper if there isn’t enough in the box (although heaven help you if your game has gone on long enough to require this)! Maybe Parker Brothers’ could have simply given this direction to those financial institutions that collapsed during the recent banking crisis, and saved us all from a lot of bother. During a marathon four-day game at a University of Pittsburgh fraternity, Parker Brothers couriered more money to the gamers to “prop up” their struggling bank: at least we can all approve of a bailout that the taxpayer doesn’t have to fund, I suppose! Compare this to Puerto Rico, a game which also requires a little thematic suspension of disbelief, but which utilises the depletion of resources as an important game mechanic, forcing players to change strategies in order to remain profitable.

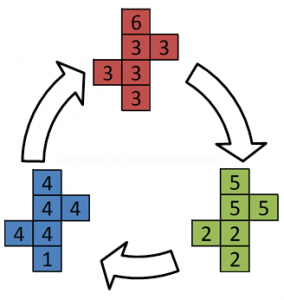

- Curiously, this same rule does not apply to the supply of houses and hotels, which are deliberately limited: the Monopoly world is one in which money is infinite but in which bricks are not. This makes it more valuable to build houses when there are few resources (in order to deprive your opponents). In actual economies, however, the opposite is true: houses are always needed, but the resources to built them change in value as they become more or less scarce. Watch the relative perceived values of the huts available to build in Stone Age to see how a scarcity economy can really be modelled.

- Also, it has a completely-backwards approach to market forces. In the real world, assuming (as Monopoly does) a free market, then it is consumer demand that makes it possible to raise capital. In the real world, the building of three more hotels on this side of the city makes it less-likely that anybody will stay at mine, but this is not represented at all. Compare to the excellent 7 Wonders, where I can devalue my neighbour-but-one’s goods supply by producing my own, of the same type.

- It only superficially teaches that “American dream” that you can get ahead in the world with a lot of work and a little luck: this model collapses outside of frontier lands. If you want to see what the real world is like, then wait until you’ve got a winner in a game of Monopoly, and then allow everybody else to re-start the game, from the beginning. It’s almost impossible to get a foothold in a market when there’s already a monopoly in existence. This alternative way of playing might be a better model for real-world monopolies (this truth is captured by the game Anti-Monopoly in a way that’s somehow even less-fun than the original).

You might shoot down any or all of these arguments by pointing out that “it’s just a game.” But on the other hand, we’ve already discovered that it’s not a very good game. I’m just showing how it manages to lack redeeming educational features, too. With the exception of helping children to learn to count and handle money (and even that is lost in the many computer editions and semi-computerised board game versions), there’s no academic value in Monopoly.

The History

You’ve seen now why Monopoly isn’t a very good game both (a) because it’s not fun, and (b) it’s not really educational either – the two biggest reasons that anybody might want to play it. But you might also be surprised to find that its entire history is pretty unpleasant, too, full of about as much backstabbing as a typical game of Monopoly, and primarily for the same reason: profit!

If you look inside the rulebook of almost any modern Monopoly set, or even in Maxine Brady’s well-known strategy guide, you’ll read an abbreviated version of the story of Charles Darrow, who – we’re told – invented the game and then published it through Parker Brothers. But a little detective work into the history of the game shows that in actual fact he simply made a copy of the game board shown to him by his friend Charles Todd. Todd, in turn, had played it in New Jersey, to which it had traveled from Pennsylvania, where it had originally been invented – and patented – by a woman called Elizabeth Magie.

Magie’s design differed from modern interpretations in only one major way: its educational aspect. Magie was a believer in Georgian economic philosophy, a libertarian/socialist ideology that posits that while the things we create can be owned, the land belongs equally to everybody. As a result, Georgists claim, the “ownership” of land should be taxed according to its relative worth, and that this should be the principal – or only, say purists – tax levied by a state. Magie pushed her ideas in the game, by trying to show that allowing people to own land (and then to let out the right of others to live on it) serves only to empower landlords… and disenfranchise tenants. The purpose of the game, then, was to show people the unfairness of the prevailing economic system.

Magie herself approached Parker Brothers several times, but they didn’t like her game. Instead, then, she produced sets herself (and an even greater number were home-made), which proved popular – for obvious reasons, considering their philosophical viewpoints – among Georgists, Quakers, and students. She patented a revised version in 1924, which added now-familiar features like cards to mark the owned properties, as well as no-longer-used ideas that could actually go a long way to improving the game, such as a cash-in-hand “goal” for the winner, rather than an elimination rule.

Interestingly, when Parker Brothers first rejected Charles Darrow, they said that the game was “too complicated, too technical, took too long to play”: at least they and I agree on one thing, then! Regardless, once they eventually saw how popular Lizzie Magie’s version had become across Philadelphia, they changed their tune and accepted Darrow’s proposal. Then, they began the process of hoovering up as many patents as they could manage, in order to secure their very own monopoly on a game that was by that point already 30 years old.

They weren’t entirely successful, of course, and there have been a variety of controversies around the legality and enforcability of the Monopoly trademark. Parker Brothers (and nowadays, Hasbro) have famously taken to court the makers of board games with even-remotely similar names: most-famously, the Anti-Monopoly game in the 1970s, which they alternately won, then lost, then won, then lost again on a series of appeals in the early 1980s: there’s a really enjoyable book about the topic, and about the history of Monopoly in general. It’s a minefield of court cases and counter-cases, but the short of it is that trade-marking “Monopoly” ought to be pretty-much impossible. Yet somehow, that’s what’s being done.

What’s clear, though, is that innovation on the game basically stopped once Parker’s monopoly was in place. Nowadays, Hasbro expect us to be excited when they replace the iron with a cat or bring out yet another localised edition of the board. On those rare occasions when something genuinely new has come out of the franchise – such as 1936’s underwhelming Stock Exchange expansion, it’s done nothing to correct the fundamental faults in the game and generally just makes it even longer and yet more dull than it was to begin with.

The Players

The fourth thing that I hate about Monopoly is the people who play Monopoly. With apologies for those of you I’m about to offend, but here’s why:

Firstly, they don’t play it like they mean it. Maybe it’s because they’ve come to the conclusion that the only value in the game is to waste time for as long as possible (and let’s face it, that’s a reasonable thing to conclude if you’ve ever played the game), but a significant number of players will deliberately make the game last longer than it needs to. I remember a game once, as a child, when my remaining opponent – given the opportunity to bankrupt me and thus win the game – instead offered me a deal whereby I would give him some of my few remaining properties in exchange for my continued survival. Why would I take that deal? The odds of my making a comeback with a total of six houses on the board and £200 in my pocket (against his monopoly of virtually all the other properties) are virtually nil, so he wasn’t doing me any favours by offering me the chance to prolong my suffering. Yet I’ve also seen players accept deals like like, masochistically making their dull pick-up-and-roll experience last even longer than it absolutely must.

Or maybe it’s just that Monopoly brings out the cruel side of people: it makes them enjoy sitting on their huge piles of money, while the other players grovel around them. If they put the other players out of their misery, it would end their fun. If so, perhaps Lizzie Magie’s dream lives on, and Monopoly really does teach us about the evils of capitalism: that the richest are willing to do anything to trample down the poorest and keep them poor, so that the divide is kept as wide as possible? Maybe Monopoly’s a smarter game than I think: though just because it makes a clever point doesn’t necessarily make a board game enjoyable.

It’s not that I’m against losing. Losing a game like Pandemic is endless fun because you feel like you have a chance, right until the end, and the mechanics of games like Tigris & Euphrates mean that you can never be certain that you’re winning, so you have to keep pushing all the way through: both are great games. No: I just object to games in which winning and losing are fundamentally attached to a requirement to grind another person down, slowly, until you’re both sick and tired of the whole thing.

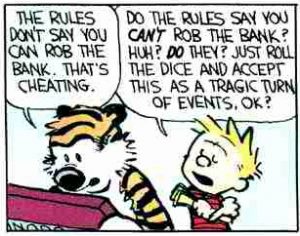

The second thing that people do, that really gets on my nerves, is make up the damn rules as they go along. I know that I spent a while further up this page complaining that Monopoly’s rules are pretty awful, but I can still have a rant about the fact that nobody seems to play by them anyway. This is a problem, because it means that if you ever play Monopoly with someone for the first time, you just know that you’re setting yourself up for an argument when it turns out that their crazy house rules and your crazy house rules aren’t compatible.

House rules for board games are fine, but make them clear. Before you start the game, say, “So, here’s the crazy rule we play by.” That’s fine. But there’s something about Monopoly players that seems to make them think that they don’t need to. Maybe they assume that everybody plays by the same house rules, or maybe they don’t even realise that they’re not playing by the “real” rules, but it seems to me that about 90% of the games of Monopoly I’ve been witness to have been punctuated at some point by somebody saying “wait, is that allowed?”

Because I’m a bit of a rules lawyer, I pay attention to house rules. Free Parking Jackpot, in which a starting pile of money – plus everybody’s taxes – go in to the centre of

the board and are claimed by anybody who lands on Free Parking, is probably the moth loathsome house rule. Why do people feel the need to take a game

that’s already burdened with too much luck and add more luck to it. My family used to play with the less-painful but still silly house rule that landing

exactly on “Go!” netted you a double-paycheque, which makes about as much sense, and it wasn’t until I took the time to read the rulebook for myself (in an attempt, perhaps, to work out

where the fun was supposed to be stored) that I realised that this wasn’t standard practice.

Playing without auctions is another common house rule, which dramatically decreases the opportunity for skillful players to bluff, and generally lengthens the game (interestingly, it was a house rule favoured by the early Quaker players of the game). Allowing the trading of “immunity” is another house rule than lengthens the game. Requiring that players travel around the board once before they’re allowed to buy any properties is yet another house rule that adds a dependence on luck and – yet again – lengthens the game. Disallowing trading until all the properties are owned dramatically lengthens the game, and for no benefit (why not just shuffle the property deck and deal it out to everybody to begin with: it’s faster and achieves almost the same thing?).

I once met a family who didn’t play with the rule that you have to spend 10% extra to un-mortgage a property, allowing them to mortgage and un-mortgage with impunity (apparently, they found the arithmetic too hard)! And don’t get me started on players who permit “cheating” (so long as you don’t get caught) as a house rule…

Spot something in common with these house rules? Most of them serve to make a game that’s already too long into something even longer. Players who implement these kinds of house rules are working to make Monopoly – an already really bad game – into something truly abysmal. I tell myself, optimistically, that they probably just don’t know better, and point them in the direction of Ticket to Ride, The Settlers of Catan, or Factory Manager.

But inside, I know that there must be people out there who genuinely enjoy playing Monopoly: people who finish a game and say “fancy another?”, rather than the more-rational activity of, say, the clawing out of their own eyes. And those people scare me.

Further Reading

If you liked this, you might also be interested in:

- Why Hobby Gamers Don’t Like Monopoly, a serious summary on Board Game Geek

- An Enthusiastic Review of My New Favorite Game, a tongue-in-cheek April Fools’ joke at Monopoly‘s expense, on Board Game Geek

- What’s Wrong with Monopoly (the game)?, by Benjamin Powell, discusses the bigger faults in Monopoly‘s economic model, as a reflection on the real world

- Cracked rates Monopoly as the worst board game ever, too

- My blog posts tagged ‘board games’

- Monopoly might be the worst game ever, says Jonathan Wolf

- A recent article by Joshua Hedlund explains that Monopoly is (still) an outdated board game (he shares a lot of my points, but I swear I’d almost finished writing this post before I discovered his)

![Ruth and Dan playing Scrabble[TM] in a pub in Leith. Ruth and Dan playing Scrabble[TM] in a pub in Leith.](/_q23u/2012/08/DSCF0454-1-1024x768.jpg)